There are huge quantities of microfilm material in the archives of organisations and institutions in…

Losing touch with the past

This week space scientists and astronomers have been celebrating the 25th anniversary of the launch of two spacecraft – Voyager 2 on 20 August, and its twin, Voyager 1, 16 days later.

Friday, 23 August, 2002, 07:47 GMT 08:47 UK – http://news.bbc.co.uk

Losing touch with the past

Technology consultant Bill Thompson is worried about losing our digital history

They were sent to Jupiter, Saturn and the other outer planets, and the coverage of the anniversary took me back to the sheer excitement of seeing what these far-distant planets really looked like.

In 1979 I was 18, and I remember seeing the first clear pictures of the great red spot in Jupiter’s atmosphere, taken by Voyager 1.

Now it has travelled further from the Earth than anything else we’ve thrown into the sky. It’s about 85 times as far from the Sun as we are and is still sending back information about conditions at the edge of the Solar System.

It may even leave the sun’s influence before its power supply fails in about 2020.

Alien record

Even without power, both craft will continue to travel into interstellar space. However if they are ever found by another intelligent form of life then they carry with them information about our planet and its inhabitants.

Each craft has a plaque, engraved with a picture of a woman and a man and some clues as to where to find our planet.

There is also a copper audio recording – a metal LP – with greetings in 60 languages and recordings of many natural sounds.

The idea is that an alien civilisation would be able to figure out how to read the record – there is even a spare needle on board – and be able to play it.

This is an interesting idea and it even seems possible. After all, making sound waves by vibrating a membrane is easy to do, as a child I remember playing records using a thorn instead of a needle.

But suppose that Voyager was being launched today. Nobody would think of putting a long-playing analogue record on board because we are now a digital civilisation.

Perhaps a CD or DVD would do instead. Except, of course, that it would not.

Even if an alien figured out that there was a sequence of ones and zeros hidden in the DVD and set up a laser to read them, they would have no idea of how the sounds had been encoded, how the constantly varying pattern of frequencies at different volumes had been turned into binary.

They would never hear human speech or whale song.

Domesday disks

It is not just the space aliens who are having problems with digital data. We have now been using computers and digital storage for long enough to have to deal with the issue ourselves, and there is a large and growing collection of unrecoverable data on our computers.

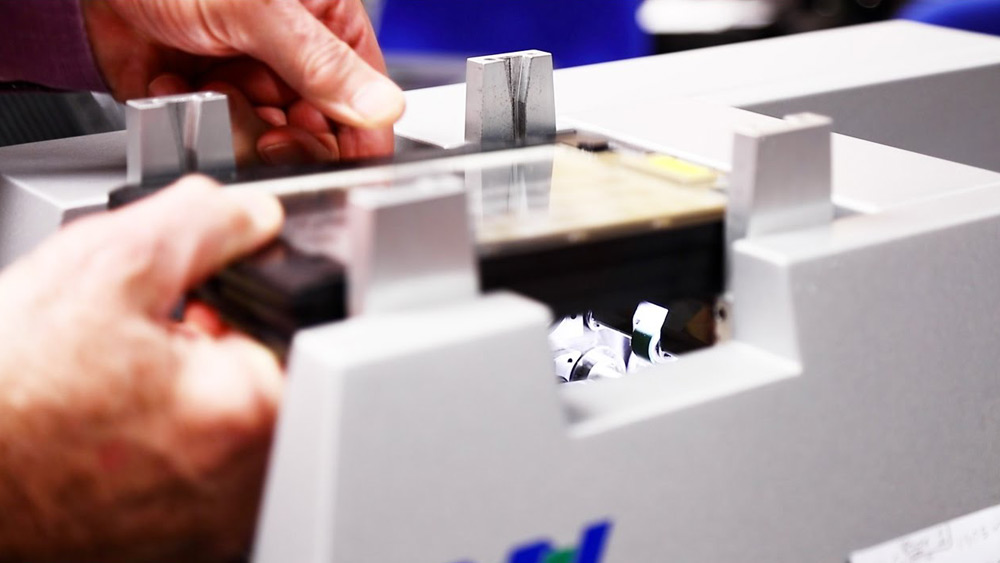

In 1986, while the Voyagers were still hopping between the planets, the BBC and Acorn Computers created the Domesday Project – two interactive video disks which were read in a specially adapted Philips VP 415 player.

It is worth being precise, because there are now very few working VP 415s around, and as a result most of the Domesday disks are effectively unreadable.

The 11th century Domesday Book may be in Latin but it can at least be seen and the words can be made out. There is no such ability with a videodisk without its hardware.

Fortunately we do know how the data was encoded on the disks and so could, if we wanted, transfer the data to another medium and make it accessible to today’s computers.

But there are millions of tapes in company and university archives which contain all sorts of undocumented file formats and this is digital data that is almost certainly unrecoverable.

Child’s play

Does this matter? If I cannot read the personnel files from a now-defunct company, then it does not really seem to be terribly significant.

Yet more and more of our personal communications, more and more of the information we deal with every day, more and more of the stuff we create ourselves, from e-mails to photos and videos and drawings, is stored digitally, often so it can be sent over the internet.

When she was three, my daughter Lili did a drawing on the computer, and I still have it and can look at it. In 50 years’ time I may no longer be able to do this, even if I remember to copy the file to every new computer I own.

What is the solution? Do we really want to print out every document on acid-free paper and archive it? I don’t think so. The point of the network is to get rid of paper, not to encourage the creation of massive new libraries.

Perhaps we just have to trust to the skills of historians and archaeologists to come. After all, many ancient languages have been deciphered from very few clues, like hieroglyphics or Linear-B.

But the stuff that matters to me personally, like my daughter’s first piece of computer art, will make it onto paper, however silly it may seem.

What you said about Bill’s column:

There should be no need to rely only on the future skills of historians and archaeologists. Librarians will be already archiving different media types with a positive view towards future retrieval.

Chris Foster, Scotland

There needs to be an obligation on designers and manufacturers of new systems to design new systems with the idea of some degree of future proofing and future systems need to be backward compatible.

Adam, UK

The problem here is not the technology, but procedures and documentation. In my previous company, very ancient files were stored with a working hardware unit, or copied onto newer systems. Data management is easy if proper procedures are in place. If you have ignorant or negligent data management staff, then even keeping things on paper won’t help you.

Jezar, England

I think this is a serious concern. The Y2K problem was left until the last minute. This issue however will, I’m sure increase in its importance over time as more and more data and becomes unrecoverable. If computers had become commercially available several centuries ago and artists and inventors of long ago stored their works in a digital format on their computers, many of today’s inventions would not exist and the art world would also have missed out on some of the world’s greatest artwork that fortunately can be enjoyed today in galleries.

Rich, UK

I am a writer and a historian and this is a problem I have worried about. My personal solution is to keep copies of all the old programmes I no longer use, and to update my backups regularly. When 5-1/2 inch disks finished, I copied all the data I had stored on them onto 3-1/2 in floppies, then to Zip disks, and now onto recordable CDs. But I still keep hard copies of key stuff. I wonder too about BBC News Online. I love the fact that I can go to libraries and see old copies of newspapers, many of them with complete runs of a century or more. Is there an equivalent for the BBC news website, I wonder?

Iqbal Siddiqui, UK

Looking back, if a widely available standard becomes outdated, it will be possible for some time to restore the information on it – vinyl and audio cassettes are examples. At present we rely on standard computer equipment to store information. I expect that files I leave on my website on the internet will be available in 10, 20 even 50 years to what ever device I attach to the internet with.

Ben Roberts, UK

Formats are an issue with computers. For example, I have games which I enjoyed playing on early computers such as the ZX81 and the BBC Micro. I still have the games, but the computers are long gone, replaced by my trusty PC which does not recognise the formats. Fortunately, emulators which run on PC’s enable me to continue to play these classics on current systems. I don’t know if emulators are available for VP 415’s, but if we are to retain this information, I feel that emulation on current hardware is the best solution – rather than trying to keep the original machines working as I’m sure that working parts will get progressively harder to find.

Steve Burns, UK

Surely if we have been capable of deciphering Egyptian papyrus scrolls and clay tablets, advanced civilisations could fairly easily work out how a CD was written? Chris

Chris Bird, UK

My daughter spent three months doodling on an old Mac, then started messing with the folders and NOW the thing doesn’t start up now but I can’t throw it out because it has all those doodles. lon Barfield, UK

The Bill Thompson column is courtesy of BBC WebWise, part of BBC Education’s ongoing campaign to teach people about the internet and how to use it. Bill is a regular commentator on the BBC World Service programme Go Digital